Georgia

When will local redistricting happen in Georgia and how to be a redistricting watchdog

Published

4 years agoon

Editor

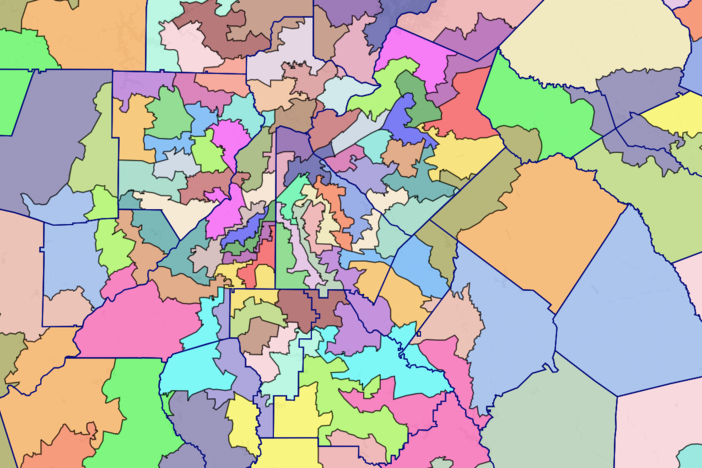

GEORGIA – Later this year, Georgia’s General Assembly will convene for a special session to redraw the boundaries of the state’s legislative and congressional districts based on data from the 2020 census.

While U.S. Census delays have pushed back the timeline for the once-a-decade redistricting process, it’s still possible to get an idea of what changes could — and should — be made to our political maps.

Redistricting will impact every Georgian’s life, from who their representatives are to who controls state government and Congress. And it’s not just Georgia that has to redraw its boundaries that will shape the next 10 years. We are keeping an eye on it all, and want to hear from you about your concerns and what you learn.

The first census results were released April 26. Those results determine, based on population, each state’s representation in Congress and the Electoral College. States will either gain, lose or keep the same number of representatives. Georgia retained its current allotment of 14 congressional seats.

This will be the first redistricting cycle in which maps don’t have to be approved by the federal government, following the 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision that ended preclearance requirements for Georgia and other states with a history of racially discriminatory voting changes.

For the next several months, the Georgia News Lab and GPB News will bring you data and stories about Georgia’s demographic and political changes over the past decade — before final numbers and maps are created. This reporting recipe will outline what data we are using, provide highlights of the redistricting process and explain what to expect from your lawmakers.

WHY IT MATTERS

Redistricting has wide-ranging implications for individuals, for elected officials and for the country as a whole. For voters, it helps determine who will represent them and their neighborhood. For politicians, it can mean the difference between easy reelection and being voted out of office.

More broadly, changing a district’s boundaries — and its voters — can alter the political direction of that district, and of an entire legislative body.

Take the U.S. House, for example. Democrats currently control the chamber by just six votes. In Republican-controlled states, redistricting could result in Democrats in competitive districts being drawn into more GOP-friendly boundaries, making it easier to flip the chamber.

In Georgia, suburban Atlanta’s 6th and 7th Congressional districts have recently turned Democratic blue after decades of being reliably red Republican strongholds. But lawmakers could change their boundaries this year so Democratic Reps. Lucy McBath and Carolyn Bourdeaux face a different, more conservative electorate in 2022.

When lines are drawn to gain political advantage, known as gerrymandering, voters’ voices can be diluted. Issues they care about may not be fully represented. Gerrymandering can also lead to an increase in the number of noncompetitive races and increase political factionalization. Redistricting is especially fraught in Georgia this time around, given the state’s growing population and increasingly competitive politics.

KNOW THE PROCESS

Drawing districts that contain an equal number of people sounds like a simple process but in fact, it can be extremely complicated. There are a lot of moving parts and considerations. Before trying to determine what districts might look like, it is important to know how the process is supposed to work — and how it sometimes doesn’t.

Fortunately, there are many good guides available. We compiled a list of readings and resources here: https://bit.ly/3nxBNBt. They cover everything from basic introductions to detailed analyses of the considerations involved in the upcoming round of mapmaking.

We’ve also included resources on the redistricting process in Georgia, the legislative committees that will draw the maps, new legal considerations in this round of redistricting, the ins and outs of gerrymandering, and efforts by some states to reduce the political influence on the process.

It is also helpful to know how the process has played out in past cycles, providing context for what is to come. In 2001, for example, Democrats were on their way out of favor and drew lines that “pushed the envelope,” according to University of Georgia professor Charles Bullock, and were eventually struck down in court.

In 2011, Republicans were in charge.

“Georgia Republicans were in good shape,” Bullock said. “If you look at the maps, they’re not the extraordinary shapes that Democrats resorted [to] in 2001 when they were desperately trying to hold onto power.”

You can also check records of past redistricting committee sessions. For Georgia, minutes (and videos) of past House redistricting committee meetings are archived here. Senate meetings are archived here.

Practically speaking, the final plans the legislature passes will consist of lists of names and numbers corresponding to what the Census Bureau calls Voting Tabulation Districts (VTDs) and Census blocks.

Census blocks are the smallest possible geographic subdivision used to create legislative districts and are bounded by visible things such as roads and rivers and nonvisible things such as property lines and city limits. These are the building blocks used to achieve the level of precision needed for proportional maps. VTDs are like election precincts within each county.

WHAT’S DIFFERENT THIS TIME?

Since the last round of redistricting in 2011, a pair of Supreme Court decisions have lowered some of the guardrails around how maps are drawn. In 2013, the court struck down a provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required required Georgia and 15 other states with a history of voting discrimination to receive approval from the U.S. Justice Department before making any change that would affect voting, including redrawing district maps. In a 5-4 decision, the court ruled that the requirement was excessive and no longer necessary.

The 2021 redistricting will be the first full cycle since the implementation of the Voting Rights Act that Georgia and other previously covered jurisdictions will not be required to submit maps to the Justice Department for preapproval.

The 2021 redistricting cycle will also be the first since another 5-4 Supreme Court decision in 2019 determined that federal courts do not have jurisdiction over claims of partisan gerrymandering. As a result, maps can now only be challenged on the basis of unfair political districts in state court, where there is little legal precedent.

Georgia is also a lot different politically than it was in the last two redistricting cycles, as evidenced by a bitterly contested presidential election that saw Democrats narrowly edge out a victory and runoff races in which they flipped both U.S. Senate seats. In the state House, Republicans have a relatively comfortable majority of 103 seats to Democrats’ 77, though there are a handful of suburban seats that could be vulnerable in upcoming elections due to blue-leaning demographic shifts. In the state Senate, Republicans hold 34 of the 56 seats with a handful of metro Atlanta districts that saw close races for incumbents.

Another consideration this time is that the census was conducted during the coronavirus pandemic, which caused delays to the data collection process and may have resulted in lower — or higher — response rates than in past counts, as well as other anomalies. Still, these are the numbers that will be used for redistricting.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

It will be a while yet before lawmakers actually start debating new maps, but there are several things you, as a citizen, can be thinking about.

First, learn who is responsible for redistricting in your state and how the process is supposed to work. Does the legislature draw the maps, as in Georgia? Or are they drawn by an independent commission? The National Conference of State Legislatures has a good set of links about processes, terminology, the law and data here.

In Georgia, the primary law governing redistricting is the state constitution. It establishes that the state legislature draws the maps and the governor can veto the plan. Unlike other states, Georgia does not set a deadline for when the process must be complete.

The redistricting process is further regulated by state code (O.C.G.A. § 28-1-1, 28-2-1 and 28-2-2), which says there shall be 180 House districts and 56 Senate districts.

Find out what guidance mapmakers will follow in drawing new districts. A guide to redistricting criteria by state is here. In Georgia, the state constitution requires only that state legislative districts be contiguous. There are no specified requirements for congressional districts, but in 2011 Georgia’s congressional districts were drawn to be plus or minus one person from the ideal district size.

In 2011, the House and Senate redistricting committees drew up guidelines that also took into account things like compactness, communities of interest, preservation of existing political subdivisions and avoiding districts that would set up contests between incumbents, a practice known as pairing.

In 2001, when Democrats controlled the process, they drew maps that pitted 24 Republican senators against each other, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported. In the House, the Democrats paired 37 of 74 Republican candidates, as well as nine Democrats and an independent.

In 2011, when Republicans drew the maps for the first time, they paired 20 incumbents. The races featured six sets of Democrats facing off against one another and four sets of Republicans.

DETERMINING WHO WILL DRAW THE MAPS

In Georgia, the maps are drawn by the Legislature. The current members of the House Legislative & Congressional Reapportionment committee are here. The members of the Senate Reapportionment and Redistricting committee are here.

Do the people drawing the maps have a personal or partisan interest in the outcome? In Georgia, they do. Several members of both committees represent highly competitive districts. Plus, the influence of the rapidly changing demographics and population shifts in the state could be diluted for the next decade, depending on how lines are drawn.

Some members of both committees, particularly in the Senate, actively promoted false claims of widespread fraud in the 2020 presidential election and engaged in efforts to overturn the outcome, as well.

There will likely be several public hearings about proposed changes, where lawmakers can hear feedback from citizens about redistricting.

When the special session is called, the legislative redistricting committee meetings will be open to the public as well as streamed online.

In the meantime, there are sites such as Dave’s Redistricting App that allow you to take a crack at creating your own maps using current data estimates.

FIND THE DATA

It will be impossible to know exactly how many people are in each geographic subdivision used to draw district maps until the census releases official numbers. Even after the apportionment numbers were released, we only know the ideal size for each district.

In the meantime, there are some data sources that can provide a rough approximation of population trends.

The data we are using are compiled from two sets of numbers. The first is the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) five-year population data broken down by state legislative and congressional districts from 2012, the year of the first election conducted on the maps drawn in 2011. The second set is the same survey from 2019, the most recent year that contains the same congressional, state House and Senate-level data as the 2012 records.

It is important to note that these are estimates that could differ significantly from the eventual census figures because of atypical response rates during the pandemic. But for now, they are the best available numbers.

You can access the tables yourself at data.census.gov. Here’s where we found 2012 data for the state House, and here are the state Senate numbers. They include the Race and Ethnicity data from Census table B02001, with “All State Legislative Districts” selected as the geography.

For the 2019 data, the state House and state Senate tables were accessed using the same parameters.

From 2012 to 2019, the average estimated size of Georgia’s 14 congressional districts swelled by about 49,000 people to 743,000, according to the ACS data. The 56 state Senate districts have grown by about 12,300 people to 185,000. And Georgia’s 180 state House districts each contain about 4,000 additional people, or almost 58,000 on average.

Here are two spreadsheets, one for the House and one for the Senate, that show demographic and population changes for each district from 2012-2019, based on the ACS data. In the coming weeks, we will add in voter registration statistics by district, county and precinct — a much better (but still imprecise) source of information about changes. Remember, redistricting in Georgia is done based on population, not voters — and not everyone eligible to vote is registered.

SHARE WHAT YOU FIND

GPB wants to know what you’ve found. Do you work in economic development and have insight into why your district or county has grown? Are you surprised at the demographic changes in your neighborhood? Let us know as we continue to report on the shifts Georgia has seen in the last decade.

Are you with another news outlet in Georgia? Use our data to localize stories for your community and reach out to see how we can partner on reporting. (We’d appreciate your crediting our work.)

These steps aren’t just for people in Georgia — as a citizen or reporter anywhere in the United States, you can follow these steps to get started on redistricting stories and understanding in your own state, too. It’s never too early to dig into the process that tracks the last decade of changes and influences the next decade of power.